HDMI was invented with a firm purpose: to banish once and for all the connection interfaces for analog and digital signals that preceded it in the consumer market. And it didn’t seem to take much effort to achieve this. By 2004, barely a year after its arrival, it was already firmly entrenched in the A/V market, and the demise not only of the SCART, the interface it was intended to replace but also of DVI, which at that time had been quite successful in A/V devices.

Since then its massive implementation not only in audio and video devices but also in many computer components has meant that we are all, to a greater or lesser extent, familiar with it. However, there are technologies associated with HDMI that have barely made their way among users. ARC is a good example of this. Despite how practical it is and how relatively easy it is to use. Let’s see what it is and what it can do for us.

Decidedly Bidirectional

We have talked about the HDMI connection interface on countless occasions. And, given its importance in the world of A/V, we are writing on it again. For this reason, the purpose of this post is not to repeat what we have already told you on other occasions, but to “put our finger on the sore spot”. And the sore spot, on this occasion, is the bidirectionality of the HDMI link.

Unlike the interfaces that preceded it, which, as you might expect, were much more limited from a functional point of view, HDMI allows the devices it links, such as a Blu-ray Disc player, a soundbar, and a TV, to “talk” to each other. This means that data does not flow only in a direction determined by the element that acts as the source and the one that acts as the receiver; information is transferred, when necessary, in both directions.

This functionality makes possible the existence of protocols such as CEC and, above all, ARC, which is the one that concerns us most. Its implementation is based on the presence in the HDMI interface of two channels, one TMDS (Transition-minimized differential signaling), and the other for the CEC (Consumer Electronics Control) protocol.

The first of these, TMDS, is nothing more than a high-speed data transmission technique over a serial link. This channel is not only present in HDMI; it is also used by DVI. Its importance lies in the fact that it is responsible for transporting the video, audio, and signaling data necessary for content to flow from the source (the device that reads it) to the destination (the element that plays it).

What makes TMDS a robust technology, and therefore a good idea is that the data transfer is carried out, from the transmitter’s point of view, using an algorithm capable of minimizing electromagnetic interference between the conductors of the cable. And, on the other hand, the receiver has a procedure for extracting temporary information from the data stream it receives, designed so that the decoding of audio and video information is carried out without errors even if the cable run is very long.

As regards CEC, which is the other protocol that benefits from the bidirectionality of HDMI, allows us to use a single remote control to control multiple devices. Of course, as long as all of them are compatible with this technology (most of them have been for a long time) and have realized that it is necessary to activate it specifically from the configuration menus of the devices involved.

How ARC works

The acronym ARC comes from the Anglo-Saxon name Audio Return Channel. This allows us to deduce what it is: a feature implemented in the HDMI 1.4 specification that allows us to use one of the HDMI connections of our TV to extract its sound and send it to the audio equipment, whether it is a soundbar, an A/V receiver or any other device.

Before the existence of this protocol, if we wanted the sound of our TV when using a video source integrated into the TV itself, such as DTT or an app like Netflix or YouTube, to go to our audio equipment, we had to connect them using a fiber optic cable anchored to the EIAJ/TosLink connectors of both devices.

What ARC allows us to do is to completely dispense with that cable and use the same HDMI link that we use to transport video and audio from, for example, our A/V receiver to our TV, to transfer the sound from the latter to the sound system. As we can see, its usefulness is, above all, practical. But this is not the only thing to take into account. The scalability of an HDMI link is far superior to that of an optical digital connection.

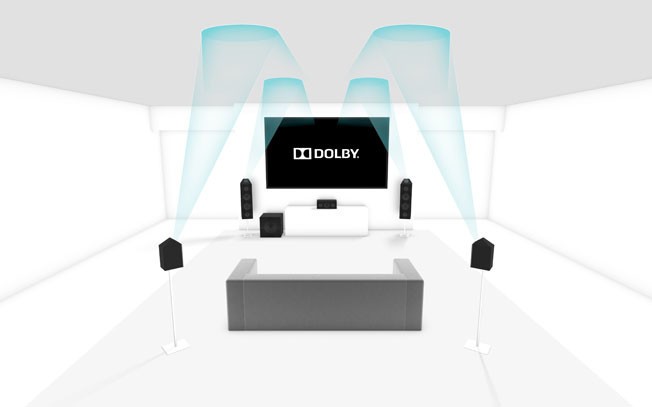

Simply put, this means that the HDMI connection interface is compatible with all the high-resolution multichannel sound formats we use today. Even Dolby Atmos and DTS:X. And it will be compatible with those coming in the future as new HDMI specifications become available.

An optical digital connection is much more limited in this scenario and is only capable of dealing with the sound formats that reigned in the DVD era (Dolby Digital, DTS, and derivatives), or other less demanding ones, but not those associated with Blu-ray Disc onwards (Dolby TrueHD, DTS-HD Master Audio, etc.).

However, the outlook for ARC is not as rosy as it seems. What I have just explained in the last two paragraphs has an important nuance that cannot be overlooked. The ARC protocol contained in the 1.4 and 2.0 HDMI specifications is only capable of carrying PCM, Dolby Digital, and DTS audio, but not Dolby TrueHD, DTS-HD Master Audio, or the later multichannel digital sound formats.

In practice, this means that even if our TV incorporates a video streaming application that allows us to access content with sound, for example, Dolby Atmos (something offered by Netflix), we will not be able to enjoy it in this format on our sound equipment, which would be desirable.

Fortunately, this limitation of ARC is about to be overcome. And it will be thanks to eARC, which is nothing more than the latest and improved revision of the sound return channel.

HDMI 2.1 goes for eARC

And it’s about time. The companies involved in the development of the latest HDMI specification have taken care to correct this very important limitation of ARC. The result is eARC, which means nothing other than enhanced ARC, a term we can translate as enhanced ARC.

It aims to allow our TVs to send any current format of high-resolution multichannel digital sound to our audio equipment, whether it is a soundbar, an A/V receiver, or any other solution. It is even capable of dealing with Dolby Atmos and DTS:X, which are currently the most demanding multichannel sound formats.

Moreover, it doesn’t matter if the high-resolution sound comes from an app installed on the TV, from DVB-T HD content, or simply from a game console or other source connected to our TV. The audio transfer to our sound equipment will be carried out without any problem thanks, to a large extent, to the enormous transfer speed enabled by HDMI 2.1 (up to 48 GB/s), and also to the new protocol used in the video and audio synchronization process. Let’s hope that eARC will finally put an end to the annoying lip-synchronization that we have all suffered from at some time or another.

However, we must bear in mind that to take advantage of all that eARC has to offer, the devices involved in the reproduction of the content must meet the HDMI 2.1 specification. This means that only A/V equipment arriving in stores this year, and probably not all of them, will be able to do so. Let’s hope they don’t take much longer.

One last important note

Two brief touches before concluding the post that may be useful to many users. On the one hand, we must take into account that not all HDMI connectors of our TV and our sound equipment are compatible with the ARC or eARC link. Those that do are usually clearly indicated with a label such as HDMI 1 IN (ARC), or something similar. These are the ones we should use.

On the other hand, we should remember that the ARC protocol is not activated by default, so we must necessarily enable it both in the configuration menu of our TV and in the sound system.

This post may contain affiliate links, which means that I may receive a commission if you make a purchase using these links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.